The following is an excerpt from my memoir On Hearing of My Mother’s Death Six Years After It Happened: A Daughter’s Memoir of Mental Illness, now available in paperback and eBook:

Amazon (Universal Link)

Barnes and Noble

Also available in Spanish! Al Oír Sobre la Muerte de Mi Madre Seis Años Después de que Ocurrió

“Steinberg! Schafer! Detention!” Mr. Cooper shouted furiously, his nearly bald pointed head bristling with a temper I had never witnessed before. That possibly no one had ever witnessed before. Normally he disregarded his students entirely and went on, in spite of the constant conversation and ill-concealed catcalls, with his physics lectures as if the classroom were empty, or perhaps irrelevant in the face of so much captivating science. But today we had somehow pierced the thick shield of his academic armor and prodded him into unanticipated and unheard-of disciplinary action. I testily kicked aside the pile of tiny paper airplanes that had grown at my feet during the course of the class and glared at my friend Josh, the one who’d gotten me in trouble. I was a good student; a nerd, most said. I’d never had detention before.

“My mom’s gonna freak,” I whispered nervously.

“Good luck with that,” he said, his face going pale.

“It might be all right. But only because it’s you.”

He grinned his characteristic sideways grin, so full of charm, so full of crap. I never could understand what my mother saw in him. Always strictly polite to his elders, laying it on thick with the ma’ams and sirs which had already gone out of fashion, he was arguably the biggest troublemaker of all of my friends, and definitely the one most likely to try to get me naked. Yet he was the only one she’d still let into the house. Would even leave me alone with him in the bedroom, staying tactfully away from my open door. Almost as if she wanted something to happen.

I gave it to her straight as soon as we emerged from the classroom, before Josh, in spite of his valiant attempt to breeze briskly down the hall with all of the craft and subtlety of one of his paper rockets, had even managed to escape from her sight. “Josh and I were fooling around in class and got detention. I have to come back after school.”

Her lips twitched. I could see the internal conflict boiling within her, picture her cheeks reddening under her makeup as we tiptoed through the crowded corridor, drawing furtive glances from curious students. I didn’t blame them for staring. It wasn’t every day you witnessed an otherwise fairly normal teen-aged girl being escorted to class by a conspicuous and over-dressed middle-aged woman. Kids I didn’t know would pounce on me in the bathroom, nearly dissolving into hilarity at finding me for a moment alone and ripe for ribbing. “Aren’t you the girl whose mother has green hair and comes to school with her?” they would snicker.

“It isn’t really green,” I would argue. “It’s supposed to be blonde; something just went wrong during the coloring.” It was more of a greenish tint than anything. The kind you get from swimming often in a chlorinated pool. Personally, I didn’t think the hair looked anywhere near as stupid as the sunglasses. Wearing mirrored sunglasses indoors is surely not the way to avoid drawing attention to yourself when you’re convinced that your ex-husband and adult daughter are stalking you.

She gritted her teeth, grinding them audibly as if literally chewing over the idea. “Then I guess we’ll have to come back after school,” she muttered bitterly, surrendering to painful necessity.

“Thanks. Otherwise I might get kicked out,” I replied pointedly, hoping she’d catch the implicit threat of it. I’d already missed more than a month that quarter and could, according to school policy, be failed across the board purely on the basis of unexcused absences.

Someone had noticed, taken pity on me. Was it one of the string of psychiatrists my mother had sent me to, each of whom I had at length convinced that I was not the crazy one? Was it one of my teachers, someone who understood that honors students don’t suddenly stop showing up to school for no reason? Was it my guidance counselor, who had been in the office the day my mother had tried to force me to sign the papers saying I was dropping out?

They’d made arrangements, the school board had informed her officiously. One of the teachers – the English teacher I’d had freshman year – had volunteered to take me in, and if she didn’t let me come back, they would force the issue. I’d been touched. I barely remembered Mrs. Silverman; recalled more vividly the handsome, witty boy who’d sat next to me during her class and who had eventually become my first boyfriend. I wondered what it would be like to live with her, her and the other troubled student she’d allegedly taken under her wing. Who would even have imagined that a close-knit suburb could hold two such students?

Even my mother, so bold in the face of imaginary enemies, was unwilling to risk official intervention. She’d let me come back. With conditions. I can’t even guess what she told the principal and the superintendent – whether she in fact convinced them that I might be in some sort of danger, or if they merely thought it best not to chance it, never suspecting that the woman to whom they had admitted entrance was more dangerous by far than any of the nonexistent murderers she feared. But they had permitted it, this insane adult intrusion into the lives of unwitting high school students. As long as she stayed outside the classroom, not in it. Inside, they’d insisted, would be too distracting. But as a goodwill gesture they had commandeered for her a set of her own chairs, one parked outside of each of my classrooms, that she might not grow weary during her dull and lonely vigils. What kind consideration, I’d thought bemusedly. How nice that they’d made an effort to ensure her comfort.

“We’re going home now,” she announced. “You can skip P.E.”

“I still have to come back for detention, Mom,” I reminded her.

“I want to go home for lunch,” she insisted, grabbing me awkwardly by the elbow while I slipped my book-bag over my shoulders.

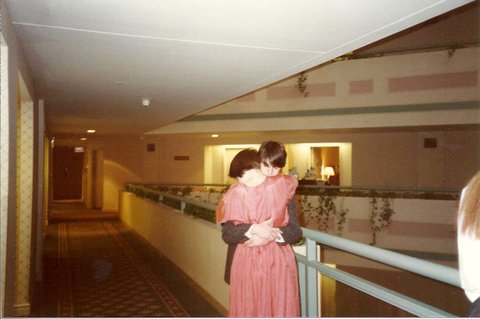

I didn’t argue. I succumbed to her clutch and followed her silently, listening to the swish of her floor-length skirt as we traversed the corridor towards the parking lot where the student vehicles were stored. We passed the vice-principal, a friendly-faced giant of a man, along the way. I nearly forgot myself and smiled. Following my first string of poorly explained absences, he had tried to be kind to me.

“Schafe!” he’d exclaim when he passed me in the hall, punching me gently on the shoulder with his beefy fist.

“Huff!” I’d answer back, grinning, with the kind of liberty in which only kids who were sorely pitied could safely indulge.

But that was before this, before I’d had a permanent, round-the-clock guardian. Now he didn’t speak; barely even glanced at us as he edged cautiously away, retreating as far as possible against the wall, as if afraid to pass too close or too suddenly. The way everyone did. I didn’t blame them for that, either. They were right to do it.

We reached the double-doors that opened onto the parking lot, barred gates of freedom before which I would have cowed had I been alone, but she approached them boldly, as if it were her inalienable right to pass unhampered through the forbidden exit. It was a closed campus, but the hall monitors stepped politely aside to let us by as they always did, even if they didn’t know about us. Parent with child. Free pass; no questions asked. Submission to parental authority was automatic, guaranteed. Indisputable.

An overcast sky was gradually divesting itself of lukewarm spring rain, sending tiny rivulets of rainwater along the curves of my skull and down the back of my neck like the tickling tendrils of an unseen vine. I’d cast the hood of my raincoat aside, as I always did now. I didn’t like the way it restricted my peripheral vision. Our windshield was spattered thickly with raindrops, but she didn’t turn on the wipers; drove instead in half-invisibility, whether in an effort to conceal or be concealed, I couldn’t say. She had covered her badly transformed hair with a plastic rain-bonnet, of an old-fashioned design I’d never seen before and haven’t seen since. It reminded me of the handkerchief with which she’d attempted to cover up her previously long and curly chestnut hair that night we’d run away from the house, only a week before my stepfather, utterly bewildered at the sudden turn of events, agreed to move out. It hadn’t done much to alter her appearance. I was noting carefully now the effectiveness of her various disguises. Preparing myself for when I needed one.

She fixed us sandwiches, grilled cheese and tomato, the butter-browned bread and melted cheddar infusing our kitchen with a near-heavenly scent. I hesitated before biting into mine, unsure if the meal would be suddenly snatched away, as my breakfast had been, on suspicion of it being poisoned while her back was turned. And unsure also, if one of these days it would be she who had done the poisoning. But she sat down and ate with me, apparently satisfied with the attentiveness of her own preparation, and I took that to mean that my lunch was safe. I wondered whether my dinner would be.

At two-thirty I packed up my homework and reminded her that we needed to go. “In a minute,” she said vaguely, sitting taut and erect on the sofa in the hip-hugging jeans she’d changed into and snapping briskly through the pages of a woman’s magazine. By a quarter to three I was nervous.

“We’re going to be late,” I said.

“We’re not going,” she yawned with affected nonchalance, rising casually from her seat to check the lock on the front door.

“I have to go, Mom.” Inside I was panicking. “I can’t let Josh sit for detention by himself.”

Even the mention of her favorite didn’t move her. “Then you shouldn’t have gotten detention,” she answered blithely, nodding to herself in undoubting affirmation.

I inhaled so sharply that my lungs burned with the force of it. Rose slowly from the table where I’d been studying. Deliberately donned my lavender raincoat, my hands shaking, sweat forming along my hairline like condensation over a steaming pot. Chose my words carefully, not wanting to suggest more than I meant.

“I am going to school.”

I nudged past her to the door, placed my hand on the knob, and gave it a yank. She yanked back, all of her considerable might concentrated on the bones of my wrists, dislodging my grip from the door and sending me crashing through the sheetrock, leaving a nearly woman-sized hole in the wall.

“What do you want from me?!” she yelled nonsensically, as if I were a disobedient child having a fit of temper.

“I want my life back!” I shouted, conscious of the melodrama of it, my pathetic cry, but aware, too, that there was no elegant way to express what I wanted. And no hope of making her understand it even if I found the words with which to explain it.

She didn’t answer, but swung me forcibly around again, causing me to hit the opposite wall of the foyer sideways, leaving a smaller, skinnier trench in the sheetrock. And then grabbed me by one hand, dragged me out to the car, and threw me inside as if I were an uncooperative luggage bag that had been carefully packed but still refused to clamp shut.

I swallowed, rubbing my wrist, relief flowing through me like the midsummer rainshower that so briefly releases the nearly constant tension of northeastern summer skies. I could still make an appearance at detention, might still be able to graduate on time and get out of this hellhole once and for all. She backed blindly out of the driveway and took off, far faster than usual. But not in the direction of my school. Towards the border, the state line.

“I could take you away,” she’d told me once, smugly, after the first time I’d made a break for it and had to be hauled forcibly home. “Take you to the airport and fly you anywhere I want to; somewhere no one will ever find you. And I am your mother and there is absolutely nothing that anyone could do to stop me.” She’d smiled complacently, humming cheerfully under her breath. Pleased with her cleverness, the infallibility of her plan, her power.

I held hard to my seat and harder to my fear. I focused on it, drew strength from it. I didn’t speak. In silence I awaited an opportunity, a happenstance, a careless moment, while she screeched around wet, sandy curves, slamming me sideways, partly restrained by the seatbelt that was intended to ensure my safety but which was hemming me in, trapping me in the car with her like a circus animal in a travelling cage.

“You want a life?” she snarled unexpectedly as we approached a glaring red stop sign, barely tapping the brakes. “I’ll kill us both!”

But my left hand was already on the latch of the belt strapping me into the vehicle; my right hovered by the door handle. I felt her fingers snatching at the vinyl of my jacket as I jumped and rolled uncontrollably out onto the pavement. I heard her cursing violently behind me as the car shuddered to a noisy halt. The backyard backwoods of New England sprawled out before me and I sprinted into them, clawed my way through branches and brambles and pricker-bushes, and came at last to a tall wire fence that I climbed awkwardly, my full-grown feet too large for its twisted footholds, and then jumped, catching my jeans on its pointed peak and tearing them nearly the length of the seam, scraping bits of the soft flesh underneath.

I stopped. Listened. No sound of pursuit came to my ears. I stopped breathing. Listened again. Scanned the sky and tried to judge my direction from the clouds hiding the sun. Took a tentative step, my footfall crackling the underbrush. Listened again and heard nothing. Looked and saw nothing, nothing but trees and bushes and pine needles and the slivered remnants of last autumn’s leaves finally freed from the cover of snow.

And then began trudging the miles through the woods back to town.

I didn’t make it to detention. I covered my ripped pants with my jacket and dragged my torn, tired body back through the deserted hallways of the school, leaving dirty footprints on the freshly polished floors and fingerprints on the classroom doorknob that rattled uselessly in my battered hands. Josh told me later that Mr. Cooper hadn’t shown up, either. Apparently he’d forgotten all about assigning us detention. Had viewed it, perhaps, as a temporary, meaningless distraction from an important lesson in physics.

* * *

“Detention” is an excerpt from my memoir On Hearing of My Mother’s Death Six Years After It Happened: A Daughter’s Memoir of Mental Illness, now available in paperback and eBook.

Amazon (Universal Link)

Barnes and Noble

Also available in Spanish! Al Oír Sobre la Muerte de Mi Madre Seis Años Después de que Ocurrió

“Detention” is also available as a FREE eBook:

Amazon.com

Barnesandnoble.com

Itunes.com

Lulu.com