I’m driving east again on Route 18, a rural highway that runs south of the interstate through South Dakota. It’s a good road; quiet. Like many regions of the Great Plains, this area is dotted with reservation land. To those of us who are acquainted with American Indian history, the names of the places you pass along the way ring with bitter familiarity. The town of Pine Ridge, named for the former Indian agency in which Native American affairs were administered. Rosebud, the reservation that gave its name to certain branches of the Lakota, now often collectively known as the Rosebud Sioux. Wounded Knee, site of the massacre that’s generally conceived as marking the end of American Indian resistance to white settlers and their way of life.

Traveling through this historic section of the country makes me both happy and sad. Happy that the Native Americans still have land to call their own. Sad over the lengths to which they had to go to defend it. Happy that the peoples who were here before us still retain portions of their culture and heritage, and a remnant of their sovereignty. Sad, because of the conditions in which they retain them.

I visited Wounded Knee as I was working my way west towards Rapid City. Like the fiasco at Sand Creek, the 1890 “battle” that transpired there is often termed a massacre. What other term would you use to describe the slaughter of women, children, and largely unarmed warriors?

As I pulled up to this comparatively obscure landmark, a Native woman and man immediately approached my truck. They welcomed me effusively to the site, then directed me where to go and what to see. There wasn’t far to go, or much to see. The memorial of the massacre is a weather-worn and faded sign at the edge of a field…

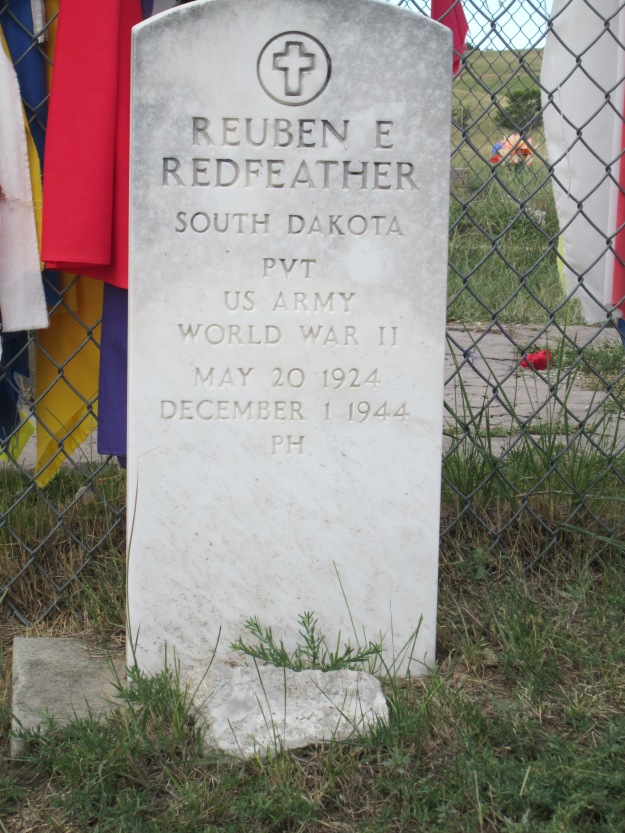

A gated patch of cemetery, containing the gravesites of more modern Sioux warriors, several of whom died in service in World War II…

And a ragged-looking museum, selling souvenirs.

I soon grasped the reason behind the effusiveness of the greeting. The man and woman held up trinkets of their own design for me to examine, perhaps to buy.

“You see, there isn’t much work around here,” the woman explained.

No, I thought. I imagine there isn’t.

As you drive through this broad stretch of reservation land – the eighth largest in the nation – you notice two things. One, the settlement is quite obviously poor. The towns are lacking in storefronts, the houses are dilapidated, the cars and trucks are rusty and old; the people, even, wear the downcast look endemic to those stricken by a lifetime of poverty. You witness them walking along the highway, those who don’t have cars or bicycles, in the blazing summer sun. I noticed that some of them were lugging bags of groceries in their hands or on their shoulders. I wondered how far they’d had to walk. I never even saw the store.

The second thing you notice is that these people, individuals though they are, truly do constitute a separate nation within the nation. Yes, many of their laws are similar to ours, but then, that is true of most modern nations. There are many Native Americans, of course, who do not live on the reservations, who have not chosen to remain in that kind of life. But among the faces of those who have, you plainly perceive a people. They still retain the characteristic and utterly unique appearance of Plains Indians; they still, in spite of nearly four hundred years of governmental efforts to consolidate and homogenize them, resemble a tribe.

The visitor center at the Crazy Horse Monument, a hundred miles southwest of here, contains a large and rather elaborate museum of Native American artifacts. Along with the spectacular headdresses for which the American Indians are perhaps best known, you can view beautiful beaded garments for both women and horses…

A sample tipi and sweat lodge…

Even an traditional “winter count,” complete with drawings, by means of which many of the native tribes tracked the history of their people.

These are not the objects of a poor people. These are the objects of a people with leisure and wealth.

Tucked away in a corner of this vast building I spied a book, a three-hole binder filled with pictures of the various flags of the surviving American Indian nations. Beneath most of them were written the historical territories and current population of each of the represented tribes. Some of them – particularly the eastern tribes – consisted of very few members. I suppose this is because the eastern tribes – those who did not escape to the West or into Canada – had a longer history of contact with white men, and their populations were therefore decimated earlier and to a greater extent. I would imagine, too, that among those who did survive, the genealogical records are more complex and difficult to unravel because several more generations have passed since they wandered freely over their own part of the continent.

By contrast, the Plains and other western tribes were forced off of their native lands almost in modern memory. Their history is not confined to some distant and largely unwritten past, in retellings reconstructed by white men alone. Although they ultimately lost the war to maintain their land and way of life, they succeeded in ways their eastern counterparts often did not, because it was the western Indians who truly captured the white American imagination. They had names, individual personalities, identities that conveyed that Native Americans were more than merely a mass of “red” enemies. Who will ever forget Sitting Bull or Geronimo, Chief Joseph or Captain Jack? They were leaders, warriors, rebels, even showmen; they earned both the settlers’ and the government’s respect. They were not just “Indians.” They were people.

Perhaps this is why the vast majority of reservation land is out here, in the West. Not only because there were fewer whites to want the land, but because the Indians of the West fought harder to keep it. They had to. By the time the war against the Indian reached the plains, Native Americans knew with dreadful certainty that this was their last stand; their last chance to retain their native ways, their peoplehood. They had little choice but to fight.

Most of the eastern tribes could have had no such foresight. This is perhaps why, for example, there are currently only about eight hundred Mashantucket Pequots, some of the first native New Englanders. The tribe did not even receive federal recognition until the 1980s. I actually knew that even before I saw the book of flags because this was how Foxwoods Resort Casino in central Connecticut – one of the first and still one of the biggest of its kind – came to be built. As independent sovereign states, recognized tribes are permitted to operate gambling enterprises on their own land in states that otherwise prohibit gaming. This development has been a terrific boon for native peoples, and has also provided an additional incentive for nearly extinguished tribes to reestablish themselves in the last twenty years. Indeed, in many parts of the East, casinos are often the sole visible reminder that Native Americans still live among us. Yet small as these tribes are, they are nonetheless difficult to forget when so many of our cities and states – like Milwaukee and Chicago, Massachusetts and Connecticut – bear derivatives of their names.

But here in South Dakota, where a substantial portion of the land is given over to reservations, and where Native Americans comprise nearly nine percent of the population (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/46000.html), the tribes are much larger, and very much in the public eye, as they are in a handful of other places in our shared nation. As many as a hundred and seventy thousand Sioux, more than three hundred thirty thousand Navajo, including those of mixed tribal designations (http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf) still reside in what is now the United States of America. Overall the remaining American Indians number nearly three million people, and comprise roughly one percent of our population – the smallest by far of our defined minority groups.

Yet they’ve survived. They have naturally lost much of their native culture, a process that began even before they were restricted to reservations. What remained of their historic modes of existence has also largely vanished, a change that commenced with the settlers’ invasion of the Plains and that has, of course, continued throughout the decades of what we term progress. Even without white interference in Indian affairs, it is difficult to imagine, in the twenty-first century, that the Plains Indians would be making cell phone calls while hunting buffalo, and watching satellite TV in tipis.

Yet it is equally difficult to imagine that, at one of the most saddening, sobering sites in American Indian history, some survivors are reduced to selling trinkets. You can’t blame them for doing it. Man’s first need is always to feed his belly. Honoring the history of your people loses much of its importance when your children are going hungry.

And there is something surprising, even baffling, about the degraded state of the Sioux in this area. Because when you’re traveling through the rest of South Dakota, you cannot help but become aware of just how much work is available there. Institutions as huge as Capital One advertise for help on the radio, the radio stations advertise for help on the radio; over and over you hear businesses pleading for workers to fill positions for which experience is “helpful, but not required.” And once you’re in the cities, the need for labor becomes even more apparent. The fast food restaurant chains, instead of advertising their specials, virtually all seem to post “Help Wanted” on their outdoor marquees. Motels post signs seeking maids and janitorial staff. These may not be the best jobs, but they’re jobs – entry-level positions that most anyone can obtain. One Walmart I saw was hiring clerks at $10.50 an hour. Not a grand sum, certainly, but considerably higher than the Federal minimum wage of $7.25, and higher, even, than the California minimum wage of $9.00 per hour. That’s a living wage in a place where you can rent a one-bedroom apartment for less than $500 per month.

Curious to see if my impressions were correct, I looked up the unemployment rate in South Dakota, and sure enough, it’s between 3.1% and 3.7%, depending on the locale – a rate so low that you can barely call it unemployment, particularly when you compare it to the current average Federal rate of 6.1% (http://dlr.sd.gov/unemploymentrate.aspx).

South Dakota seems to be one of the few places in the country where there’s plenty of employment to be had, yet for the Native Americans on the Pine Ridge Reservation, “There isn’t much work around here.”

The woman wasn’t exaggerating. I decided to look up the statistics on Pine Ridge, and they were even more horrifying than I had suspected, with an estimated 80-90% rate of unemployment and the second lowest life expectancy in the Western hemisphere (http://www.re-member.org/pine-ridge-reservation.aspx).

The statistics for the Navajo, the massive tribal group that occupies a section of Southwestern desert hundreds of miles from here, are nearly as staggering, with 42% unemployment and 43% of the population living below the poverty line (http://navajobusiness.com/fastFacts/Overview.htm).

Yes, the Native Americans have survived. But here in the West, at least, they have not thrived. Somewhere there is a disconnect between their countries and ours, between American life and Native American life. Somehow in losing their land and their livelihood, one might have expected that they would at least have gained the benefits that the modern-day United States has to offer. Yet on many of the reservations, this does not seem to be the case.

It is true; the Native Americans are their own people, members of a world they can call their own. Unfortunately, for many of them, it is a Third World, enclosed tightly – and perhaps irrevocably – within our First.

* * *

If you would like to see more photos from my cross-country travels, please follow my new Pinterest account at http://www.pinterest.com/lorilschafer/.

For updates on my forthcoming memoir The Long Road Home, which I am drafting during this road trip, please follow my blog or subscribe to my newsletter.

utterly fascinating Lori and intriguing why their pride and self determination is so strong that they will maintain their own lifestyle come what may. Contrast with those vast casinos which seem to be the epitome of exploiting the benefits of a rapacious neighbouring population. Maybe it’s a generational thing and their children will take advantage of the possibilities next door. And in such inequality extremism can breed. They may live outside the rest of the S but I’d bet a tin of bucks the FBI have the place tapped. MI5 certainly would over here.

LikeLike

I actually wonder whether they’re truly aware of the difference on a deeper level. It may be apparent to an outsider, but if you’ve lived a certain way all your life, you might just accept it as normal without even questioning whether there might be better opportunities elsewhere. I personally can see the appeal of self-determination, and I’m inclined to think that I myself would be willing to sacrifice a certain amount of material comfort in order to maintain it. But there’s a limit. Of course, we don’t know the details of native cultures or family lives, and there may be pressures we simply don’t understand. Other tribes, such as the Cherokee, have done quite well with mixing in with American society and still retaining their heritage. I’m quite convinced that there’s a reason for the overwhelming poverty on many of the reservations; I just don’t know what it is :(

LikeLike

It’s a truly fascinating subject and you’ve written about it so sensitively. When you’re part of the benefitting part of a modern society with some dodgy history that helped your society be the success it is today, it is often difficult to look back with such honesty. I look at the results of the British Empire and mostly cringe. I can see that not everything about it was bad – overall I think the common law is a good system of justice – like democracy hopeless but better than anything else – but the utterly ruthless exploitation for the benefit of these small islands of so many people, the writing of the map, especially in Africa and the Middle east that, in large part is at the root of so many of today’s conflicts these things make me feel ashamed. I try to point this out in connection with my dad’s letters from Palestine but the way you’ve written about the native Americans and their plight puts my humble little attempts into the shade.

LikeLike

As usual, you’re far too modest, Geoff :) But yes, this post made me have the same thoughts about world history. It’s very easy to look back with regret at what our ancestors did when they were the conquerors and we the beneficiaries of their questionable if not outright horrible deeds. But if we had it to do over, few of us, I fear, would choose to trade places with those who are suffering now from our government’s mistakes. In any case, I don’t think the British Empire is all that much to blame. Without that, there would simply have been a vacancy for some other empire to fill – one that perhaps would not have conferred the benefits of justice and law that English rule did. It’s interesting also to note that many, if not most, of the world’s great problem areas are in countries that lack united systems of government – those containing tribal groups, if you will. Could white settlers have overpowered a united front of American Indians or Australian aborigines? Empires may have taken advantage of those situations, but they didn’t necessarily create them.

LikeLike

I expect it comes down to Mao and the power of the gun. E white settlers had the benefit of years of fighting to hone both technique and technology and were usually in,y defeated (eg Kashmir and Afghanistan) because of terrain and tenacity and even then eventually succeeded. As to a worse conqueror well, true, no one would have widened the Belgium or Portuguese on anyone! The tribal issue, taking Iraq as an example with a mix of Shia Sunni and Kurd is very much a British construct, based on the belief that having warring tribes within one system makes it easier to control. And then the overarching control goes and all the suppressed problems surface. Ditto Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe.. The list in Africa is endless and it’s our Grand Design at root. B*****r.

LikeLike

You’re much more of an expert on political-type stuff than I am, so I guess I’m going to have to take your word for it! :)

LikeLike

It is a bit of a passion, that’s true though I often get ahead of myself

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. This fills quite a few gaps. I came across a town here in Puerto Rico where the locals were just standing around, with the same looks on their faces.

LikeLike

I was surprised to learn that Puerto Rico, in spite of having what’s considered a “high income” economy, has a poverty rate of close to 45% (http://qz.com/125654/puerto-rico-is-living-an-impoverished-debt-nightmare-reminiscent-of-southern-europe-or-detroit/), twice that of the poorest state (Mississippi).Scary stuff!

LikeLike

Sobering. And how far along was Crazy Horse?

LikeLike

Looks about the same to me as he was last time I was there, maybe ten years ago. Here’s the picture I took if you’re curious: https://lorilschafer.com/2014/09/02/they-call-it-rapid-city-because-if-you-dont-hurry-you-might-miss-something/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not much different from my 2008 visit! Maybe a century now, it will be finished.

LikeLike